Cottontails

by Rob yates

Jim was trying to clean leeks at the sink, watching white tails of rabbits dart in and out of his vision. It was long into evening. The light from the kitchen window left a neat, orange rectangle on the lawn, and this is where the rabbits could be seen, rushing through on their way to something else. Beyond that orange glow, the rest of Jim and Alison’s garden tripped into darkness. Jim knew it by feel, the feel of increasingly untamed grass beneath his strapless garden shoes as he shuffled away from the house. Alison knew it by smell, the smell of Jim failing to clean up after his dogs.

They called them Jim’s dogs because Jim was the only one who had wanted them. He’d brought both dogs home in a crate that cost more than the dogs themselves. He brought them home despite Alison having forbidden it, then challenged her to return them to the shelter. It occasioned one of their most violent rows. When Jim told the story of their fight he did so expecting people to find it amusing, but was disappointed when few did.

One of the dogs had disappeared; a beagle-terrier cross, rancid breath, weak eyes. It had forever been vanishing into hedgerows and reappearing in villages five miles down the road. This time it had failed to reemerge at all. It had been gone more than ten days.

The other dog was an old collie with greying fur and a collapsing liver. They had to feed it a pharmacy of pills each week, pills which either caused or failed to prevent diarrhoea. This dog was currently sleeping somewhere it wasn’t allowed, but Alison hadn’t yet discovered it there and Jim left it to do anything it wanted. He was convinced it was going to die soon. When they argued over dog discipline, Jim said he wanted to give the dog as much freedom as possible in its final days, but he’d always been hands-off. Three weeks after he’d brought it home, and the first time they’d walked it in the town, the collie sank its teeth into the calf of a passing child. They never knew whether this behaviour was uncharacteristic or not, because Jim never walked it beyond the garden after that. Fatty, painless lumps were now developing all over the dog’s body. The vet had told them not to worry, but there was no way in Jim’s mind this could be a good sign. The old pup was riddled with something.

Jim couldn’t count the rabbits. There were simply too many, too fast. He cycled through theories as to why they were appearing in such unprecedented numbers.

Theory I – The disappearance of one dog and the imploding health of the other had emboldened them. They no longer feared the house or the lawn. Nothing that lived here now could chase or harm them;

Theory II – Like migrating birds, they sensed something in the air that humans couldn’t, some magnetic disturbance in the ether, a bending intensity. Whatever it was, it was driving or drawing them here;

Theory III – Something in the woods had released them all at once, accidentally or otherwise. They were revelling in new found space;

Theory IV – He was hallucinating vividly;

Theory V – Something in the woods had frightened them. They were running blindly in any direction. This was a glimpse of their panicked flight.

Jim had other theories, but these were the ones that kept resurfacing.

Alison had been outside all day. Jim knew she was in her shed, even though he wasn’t allowed in there any more. When he walked out to throw vegetable skins onto the freezing pile of food waste by the back door he looked up and caught a brief readjustment of light in the shed’s only window. It was Alison adjusting her work lamp, the bright, burning bulb that Jim had warned would eventually ruin her retinas. She said she needed it.

Now, out of sight of everyone except herself, she stood at her workbench, upon which she’d placed three plastic bowls. Each bowl contained a pool of clear liquid. To her right, an open box of dead crickets, the type you feed to snakes and tarantulas. She’d negotiated a discount with the pet store owner by buying in bulk. Under her bench were numerous, unopened bags of preserved bugs.

Alison wore an asbestos-grade face mask, chemistry lab goggles, and rubber gloves. Using tweezers, she dropped a dead cricket into each of the waiting bowls, then leaned in close to note the effects.

One cricket gradually lost its rust-brown shade, taking on instead a sickly translucence. Its shifting colour gave the impression that it had paused, temporarily, on its way between two separate planes, unsure as to which it would eventually choose. A few legs detached and drifted away from the body but, for the most part, it remained intact.

The middle cricket fizzed and sputtered, causing thin ripples to shudder out towards the edge of its bowl. It dissolved relatively swiftly, just as Alison had predicted. She hadn’t really needed to test this one. It was more for her own viewing pleasure. She watched the bug melt into bubbles, like hot butter.

The third bowl was unusual. The cricket appeared to have soaked up the liquid, which had disappeared rapidly, though the insect’s form remained unchanged. For a moment, Alison thought she might be witnessing a miracle, the sort she’d never be able to explain or convince anyone of. The cricket had kept its shape, its colour. There was no discernible shift after having sucked in all that corrosive solution. It was unharmed, neither thirsty nor satiated, perfectly inert.

But then Alison thought to inspect the bowl more carefully. She realised that the plastic had been partially dissolved. The liquid had eaten through to the table beneath, escaping through a newly formed crack and dispersing across the workbench, where it had continued to gnaw through the old knotted wood. She moved the bowl to one side and ran a gloved hand over the area of spillage. Small threads and alleys of corrosion had appeared in the table top, though they followed no clear pattern. She wondered if the liquid corroded along invisible seams of weakness, or if it burrowed straight into the first thing it touched.

It was getting too late. At some point she would have to face dinner. Every time she allowed Jim to cook they ate closer and closer to midnight. He thought today was their anniversary, so he’d offered to play chef, and she’d accepted because she wanted to spend as much time as possible this evening in her shed, making living things, or things that had once been living, disappear.

It wasn’t their anniversary. Jim was off by months. His grasp on dates had slipped momentously over the past year, something they both took advantage of. It gave each of them license to overlook days they’d rather forget. Jim would forget birthdays, or pretend to forget birthdays, of people he’d never really cared for. Alison allowed memorial days to pass unmarked so that they didn’t have to sit, light candles, and talk about people who weren’t there anymore.

Jim had become distracted by the darting white tails of the rabbits. He’d been cleaning the same leek for what could have been hours. It didn’t matter, he thought. Rinsing the outside of such a vegetable rarely makes a difference. Once you cut through the leathery skin into the layers beneath you always find packed granules of dirt that need to be individually cleansed. The leek is such a tidy looking crop at first glance, so easy to handle and slice, but they are deceptively grimy. He wanted to get everything into the pan, get it bubbling and soft, cover it in oil and burn off all the microbes. What’s the point of washing when we have fire? He left a pan on the stove and walked out again to add more scraps to his compost pile.

Alison came out of her shed, removed her goggles and mask. She paid attention as the chemical tang around her nose and mouth was displaced by a clean but savage cold. She inhaled deeper than she needed to, wanting to enjoy this odourless spell, but a small shift in the wind brought instead the unmistakable spoil of dog shit, frozen but still pungent in the grass.

Jim was by the back door again, knocking an empty plate over a growing mound of fruit rind, moulding egg shells, slops of last night’s stew. Alison had given up telling him he couldn’t throw food waste there, right by the porch for everyone to tread through the house. She let the foxes and the rats and the one surviving dog deal with it. Anything left over she’d shovel up and tip into the boot of Jim’s station wagon when he was asleep. He hadn’t touched the car in months, might never touch it again, but if he did there would be something unpleasant waiting for him.

Now he was peering sideways at the lawn with its orange square of light. Something there was holding his attention but Alison couldn’t work out what it was. Perhaps he was still looking for his dog. She could see his lips moving. He was talking to himself. His trouser zip was undone and he’d neglected to button up his coat, even though he’d now been standing there for over a minute. Eventually, he turned to go back indoors, catching sight of Alison as he did so. He grinned at her in the dark, then set about waving his arms in an elaborate series of mimes, something about dinner. Their son had been non-verbal for most of his life. They’d all done a lot of miming over the years, but the older Alison got, the less patience she had for it.

‘Stop it,’ she said. ‘Talk like a normal person.’

‘One hour,’ Jim said, refusing to drop his idiotic grin, then ambled back inside, leaving the door wide open. Alison watched as he turned left into the living room, not right into the kitchen. She’d have to cook something herself.

Jim sat down and continued to think about the rabbits. Wildlife tracking technology had come a long way in recent decades. Satellite tags could be mass manufactured. They could be tacked to entire flocks of birds, endless birthing turtles, migrating beasts of all shapes and sizes. Scientists said that never before have humans had such panoramic insight into the movements of animals, but the more we learn the less we understand, they said. Zoologists kept discovering patterns of movement they couldn’t account for, in species they previously thought they knew. Jim couldn’t remember where he’d read all this, or which species were confusing migratory experts. He didn’t think cottontail rabbits had been mentioned. He wondered how he might get his hands on a GPS tracker, or a bag of them. Did they market them for civilian use? Stick one on his dog, one on Alison, one on every rabbit he could catch, which would be none. Maybe one on him, to see if anyone was surprised by the roaming patterns he made. He might surprise himself. Someone had turned all the lamps on in the living room, but he couldn’t recall who. Alison would hold him accountable anyway. A waste of energy, she called him. A waste of skin and air. He recognised his favourite lampshade, just to his left, on the table by the reclining chair. It was ocean blue with tiny, gold rivulets running across it like spiders’ veins. When the bulb was off, the glass was cloudy and dull, but when somebody switched it on it burst into colour and clarity. He’d bought it many years ago at a yardsale, paid more than the asking price because he’d loved it so instinctively. Another purchase disapproved of. Jim couldn’t remember the animals, or why their movements had scientists so confused, but he knew exactly how much he’d paid for that lamp. Strange, the things you remember, he thought as he stood up, not entirely sure where he was.

Alison waited to see if Jim would return to the kitchen, or return to shut the back door. He did neither. Down the hill, towards the far end of their drive, the neighbours’ donkey let out a great, tortured braying in the dark. It sounded alarmed, but Alison always thought it sounded alarmed. Who or what was padding around the bottom paddocks to set it off at this hour? Donkeys were better than dogs at signaling when someone was near. Dogs were too trusting, so easily led.

She went back inside to dispose of her insects and acid. Two of the crickets were still there, though the translucent one had slipped even further into its alternate, gossamer plane and was now practically see-through. Alison could just make out the minute scaffolding of its cartilage, impossibly thin wire holding a nearly vanished husk together.

She left her gloves on, took the bowls to a large plastic vat in the corner, unsealed the lid and realised too late that she’d forgotten to cover her nose and mouth. The smell that emerged from the vat made her swear out loud. She threw the contents of the bowls in, caught only the briefest glimpse of the clots of fur and fizz and gristle that drifted around in there, the tub itself almost as high as her ribs, before pushing the lid back down. She’d wanted to look at the mixture for longer than that, but she was starting to gag. She’d have to wait until tomorrow. She liked to look at it properly at least once a day, because it changed every time. Whatever she threw in seemed to alter its complexion, its texture. Even its smell varied, though never enough to be faced without a mask.

Outside, the world looked and sounded identical. The donkey cried out again, laboured and wheezing, then went silent. Whatever had startled it wandered on. Jim had emerged once more in his unbuttoned coat and his open trousers. No vegetable peel this time. He wasn’t even interested in the food waste pile, or Alison, who watched him again just as she’d watched before. She measured him with her eyes. She measured how long he had left. He was looking, as always, towards the lawn, not talking this time, just looking, expectant, but then gradually vacant, until it was clear he no longer knew what he was standing there for. Thin fingers of black smoke had started to drift across the ceiling above his head, reaching out into the night, where they became suddenly invisible. He sniffed the air like a woodland creature, sensing danger, unsure of its location. He drifted back inside in search of whatever it was that had gone so horribly wrong, but he turned left, back into the living room, not right, into the kitchen, where the smoke was starting to bunch and gather like a wave. Alison considered shouting out to him, or shouting for herself, but she decided to wait and watch, see if he could manage on his own. Somewhere in the house, the dog she hadn’t dealt with yet began to bark. Wherever it found itself when it woke, it knew it wasn’t supposed to be there.

———————————————————

———————————————————

Rob Yates is a British writer hailing from Essex. He is currently based in Charlottesville, where he is completing an MFA at the University of Virginia. He has had work appear via Agenda, Bodega, SmokeLong Quarterly, Envoi, and other literary magazines. Some of his writing can be found through www.rob-yates.co.uk.

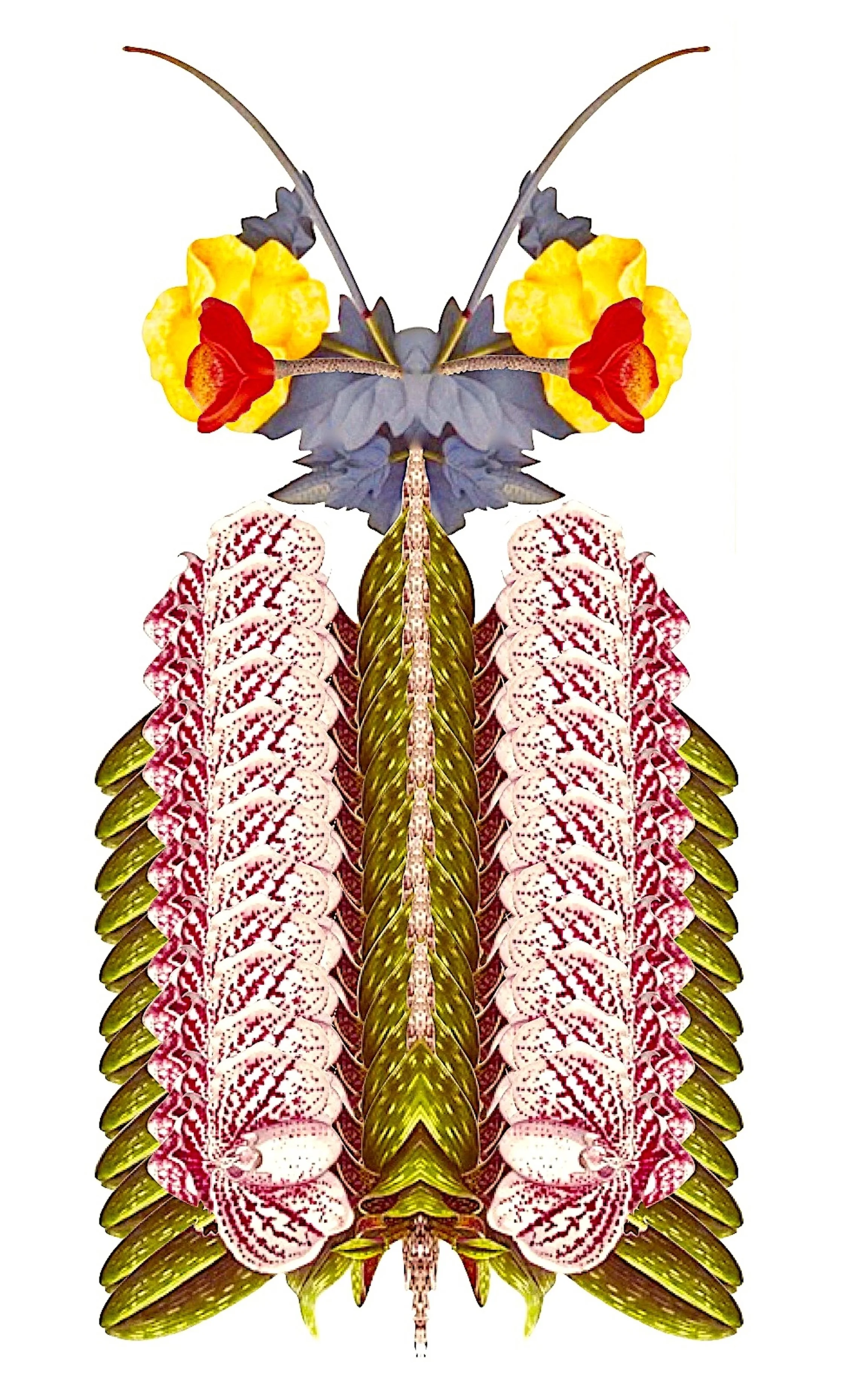

ART BY

William Wolak

The Enigma of Balance

digital collage